COP27: Australia & New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand are both at very different stages in their transitions toward electric transport than places like Europe or the UK. Neither country has any vehicle manufacturing industry, and therefore rely solely on importing vehicles to sell on the domestic market. The main places vehicles are imported from is Japan, and the Japanese marque Toyota is the most favoured manufacturer in both countries. In theory, this means that there should be less institutional pushback for EVs. However, this has not always been the case.

The Story So Far

As of September 2022, a total of 21,772 EVs have been registered in Australia. This already exceeds sales for the whole of 2021, and outstrips the total number of EVs registered between 2011 and 2020. Looking at the individual Australian states and territories, the fastest jurisdiction to electrify is the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) which is currently registering 9.5% of its new car sales as electric. This figure is well ahead of the national average. Devolution within Australia’s political system means that the state and territory governments determine their own EV subsidies and incentives, and this has generated something of a postcode lottery as to what benefits motorists can receive in return for making the switch. Some states have policy in place that significantly incentivises buying an electric car, whilst others are relatively lacklustre in comparison.

Source: Electric Vehicle Council

New Zealand has so far registered 14,368 zero emissions vehicles in 2022 - already doubling the number of EV registrations for the whole of 2021. Registrations of all vehicles have skyrocketed in the past year, with the country experiencing a 258% increase in registrations since 2017. There is roughly an equal share of new and used vehicle imports being registered, with EVs representing 6% of the overall market so far, 8% of the new car market and 3% of the used car market. An interesting similarity between the transitions in New Zealand and Australia is the rejection of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) - very few of this vehicle type are registered in either country.

Source: NZ Transport Department

The Policy Landscape

With a new Labor government being elected in Australia earlier this year, the country has pivoted markedly in how approaches electric vehicles. Prior to this, the previous Liberal-Nationals coalition government had been openly hostile towards EVs and refused to offer any federal incentive programmes for the technology. However, there are now plans for a federal tax cut for EV owners on top of the state wide incentives on offer.

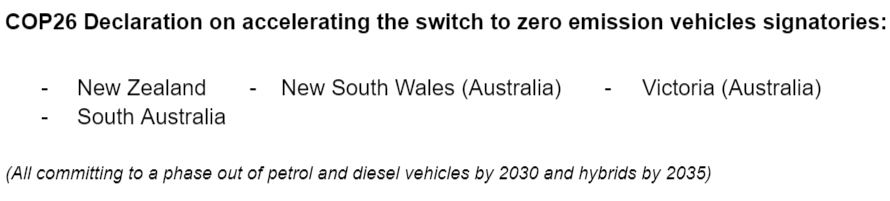

Despite strong anti-EV rhetoric from previous governments, electric cars had begun to gain a degree of organic popularity prior to this pivot. Unlike in other countries, where anti-EV governments reflect a largely anti-EV public, multiple surveys conducted across Australia show a growing popularity and understanding for EVs. This may be in some part due to the individual states' devolved powers allowing them to to set their own targets and roll out their own incentives programmes, and which saw three of the eight states or territories sign the COP26 phase out date for 2035. Australia has a long way to go but, under its new government, is showing signs of beginning to make up lost ground.

New Zealand has set a phase-out date for 2035 and continues to offer a clean vehicles rebate of $8,625 NZD for new vehicles and $3,450 NZD for used imports. A persistent problem for New Zealand’s transition has been a shortage of public charging infrastructure. There are just under 1,000 chargers in New Zealand, which tend to be focused around major urban centres. Fortunately, of those drivers who have already switched to electric 82% are able to charge from home. As a sparsely populated country, many kiwi households have off street parking and thus home charging capability is relatively high. However, there is a recognition from the government that there is a need for more public chargers. The government has a national strategy to roll out more public charge points, which is being implemented by the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority (EECA). An essential aspect of this strategy involves communicating clearly to drivers that home and workplace chargers are available and that New Zealand will rely less heavily on public infrastructure than some other jurisdictions. This is a markedly different approach to that taken in the UK and across most of Europe, and highlights the fact that there is no one size-fits-all approach when it comes to infrastructure deployment.

Moving Forward: Future Prospects

Both countries are taking positive steps towards electrification, but remain well below the world average of a 9% electric share of the vehicle market. Australia’s laggard position is particularly pronounced. It is essential that the two countries make sure they prioritise EV imports over petrol and diesel imports; the isolation of both nations, as well as their status as right hand drive countries, means they must prioritise ensuring the supply of right hand drive EVs into their respective national markets. Decisive and ambitious action must be taken to ensure both countries do not remain trailing behind the leading pack.