Talking Tax: Electric Vehicles & Road Tax in the Autumn Statement

Ahead of the Autumn Statement on Thursday, the Treasury has been briefing that the Chancellor faces decisions of ‘eye-watering difficulty’. Everyone will have to pay more tax and public services are bracing for a round of spending cuts, as the government seeks to balance its books and address the UK’s fiscal deficit.

The Financial Times recently reported that the Chancellor’s pen is poised to strike out the exemption that EV owners currently enjoy from paying vehicle excise duty (aka VED, more commonly known as road tax). As always with tax regulations, this is more complicated than it sounds. There are a range of options available to the Chancellor as he implements this decision.

So, what are these options? To what degree would each help the public purse? In this piece we examine four of these options, breaking down the pros and cons of each.

Option 1: Raise first-year VED rates for EVs

Cars registered after 2017 pay a one-off initial ‘first year’ rate of VED that varies according to the emissions output of the vehicle. This tax structure heavily penalises people who buy new polluting cars. One option is that the Chancellor could raise rates for zero emission and low emission cars so that the lowest first year rate is more than £0.

This would see the ever growing number of new electric cars on British roads begin to contribute to the public purse. However, these rates would only be paid in the first year of a car’s life. Tinkering with first year rates does not really solve the problem of lost revenue in later years.

Option 2: Increase flat-rate second year charges for EVs

Petrol, diesel, and hybrid cars registered after 2017 pay a ‘second year’ flat rate of VED. This is payable every year after the ‘first year’ rate (which is banded according to emissions).

Electric cars currently pay £0. Changing this would help address fiscal sustainability, as it would see a growing pool of EVs permanently paying a flat fee each and every year.

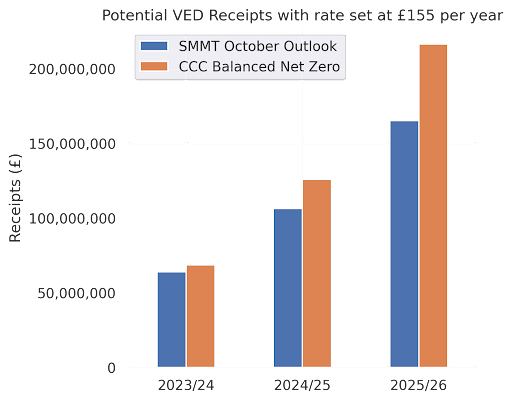

But there are two major drawbacks to this approach. Firstly, the relatively small number of EVs on British roads (about half a million electric cars, out of 34 million cars overall) means that they would only make up a small element of the tax base. Even if the Chancellor increased VED in line with the road tax that hybrids pay (£155 from their second year on the road), it would only raise around £50-60 million in 2023/24, rising to around £100m in 24/25 and £150-200m in 25/26. In the grand scheme of things, these are relatively small contributions.

The second and more profound problem is that taxing electric cars at a rate of £155/year would create a perverse tax incentive that largely favoured petrol and diesel cars. Cars registered before 2017 pay different rates of road tax than those registered since. The pre-2017 scheme’s rates are banded by CO2 emissions for the whole of the car’s life - not just its first year. Because of this, there are around 10 million pre-2017 cars which pay less than £155/year, of which the vast majority are petrol and diesel.

Given this, introducing a new second year rate for EVs would mean that drivers who choose an electric car over an old polluting diesel would be penalised for making the cleaner choice. The problem is that there are millions - around 8 million - of ‘cleaner’ pre-2017 cars paying rates of VED that are £30 or less. Given this, this option is unviable.

Option 3: Introduce a new ‘basic rate’ of VED, payable on EVs and cars registered before 2017

Since 2001, the simple idea that “the more you pollute, the more you pay” has been central to the UK’s road tax system. Increasing the rate of VED applied to EVs alone would violate this principle. To preserve it, the Chancellor could introduce what is effectively a ‘basic rate’ of VED.

Around 8 million cars pay £30 or less per year, simply because they were registered before 2017. An additionally 2 million pay £0, despite not necessarily being zero emission. If the Chancellor introduces a second year rate for EVs under the post-2017 system, he should adjust the pre-2017 rates of VED so they are not lower than the new rate applied to electric vehicles. This way, all cars would pay a ‘basic rate’ of road tax.

This would certainly help plug the deficit. Since there are so many cars paying very low rates of VED, they form a large tax base, from which small increases in rates could yield sizable revenue. Additionally, taxing these vehicles could help usher them off the road, hopefully to be replaced by newer, less polluting vehicles.

The new ‘basic rate’ would see a significant number of motorists paying more tax; we estimate there are 24 million cars on the road paying the pre-2017, CO2-banded rates of VED. Not all of them would pay more under this approach of course, but enough would that this option would raise significant public funds.

Option 4: A low ‘basic rate’ of road tax that gradually rises

If the Chancellor introduced a ‘basic rate’ of £155/year, this would hit 10 million motorists with tax rises that average £107 per vehicle. Ouch! A much more modest basic rate of £40 would see 8 million motorists facing an average rise of £21 per year. This would raise £170 million for the public purse if it was introduced for the 2022/23 financial year.

A sensible approach would be for this ‘basic rate’ of VED to rise slowly as the British parc electrifies. The key to this is that increases should be gradual, as the composition of cars on the road changes very slowly.

Option 4a: An additional rate for expensive EVs

One last option for the Chancellor is to remove the exemption from the additional rate of tax that applies to expensive petrol and diesel cars. Non-EVs are taxed at an additional rate (of £355/year for the first 5 years of their life) if they cost more than £40,000 when new.

The market for new electric cars is dominated by sub-£40,000 vehicles, in part because the plug-in car grant (PiCG) previously set a ceiling on vehicle price (before it was abolished this year), and thereby incentivised manufacturers to make affordable EVs. VED could work in a similar way and replace that lost policy signal.

Abolishing this exemption for EVs above £50,000 would be a sensible way to encourage manufacturers to produce affordable, mid-range electric cars that will eventually feed the second hand market. It would discourage them from producing models with unnecessarily large batteries that retain their value for an extended period, and thus remain relatively unaffordable for many years to come.

Final Thoughts

That the Chancellor is introducing road tax for EVs is no bad thing; they should pay road tax. Those who sell or make electric cars should welcome this news.

The Treasury is a powerful and influential department within government. If your product and industry supports Britain’s tax base, the Treasury will become your ally and advocate. That EVs are to pay road tax is a sign that they are becoming increasingly mainstream; it is a problem born out of success.

However, the details of how road tax on EVs is implemented are important. Ultimately, any of these tweaks to the system discussed in this piece should only be an interim solution. The Treasury must begin preparing a tax system for when electric vehicles are fully mainstream. This time is rapidly approaching.

Since 2001 the road tax system has been based on emissions. In the future, it could favour lighter, more efficient, or even safer cars. But these are all questions that need more time to be answered with thorough public consultation, not in response to a crisis.