What Does The New Energy Price Cap Mean For EV Running Costs?

The recent convulsions to energy prices may develop into a serious challenge to the UK’s transition to electric vehicles (EVs). As the country looks ahead to winter, with the risk of European gas shortages looming and a new government scrambling to contain spiralling bills, many people are asking two questions. How will these convulsing energy prices impact consumers considering buying an electric car? And what do they mean for the UK’s transition more broadly?

EV vs ICE Running Costs After the Cap

New AutoMotive has always been conscious that the running cost advantages of EVs are one of the biggest attractions for consumers and policymakers. Our cost saving calculator has been used by tens of thousands of motorists, who have learned just how much they could save by switching to an electric vehicle. Could the recent changes to the electricity price cap see those cost-saving figures turn negative for the first time?

Two reasons make electric vehicles cheaper to run than their fossil fuel counterparts. First, simple science: EVs are far more energy efficient than fossil fuel vehicles. Most of the chemical energy contained in the fuel tank of a petrol or diesel vehicle is lost, and only a small fraction is ever actually put to work to move the car from A to B. In an electric car, almost all of the energy contained in the battery is harnessed to move you around. Second, economics: the relative cost of electricity, petrol and diesel mean that EVs work out significantly cheaper per mile driven. As petrol and diesel prices grazed historic highs of £2 per litre earlier this year, we calculated that driving a mile in an EV would cost a fifth as much as it would in a petrol or diesel car.

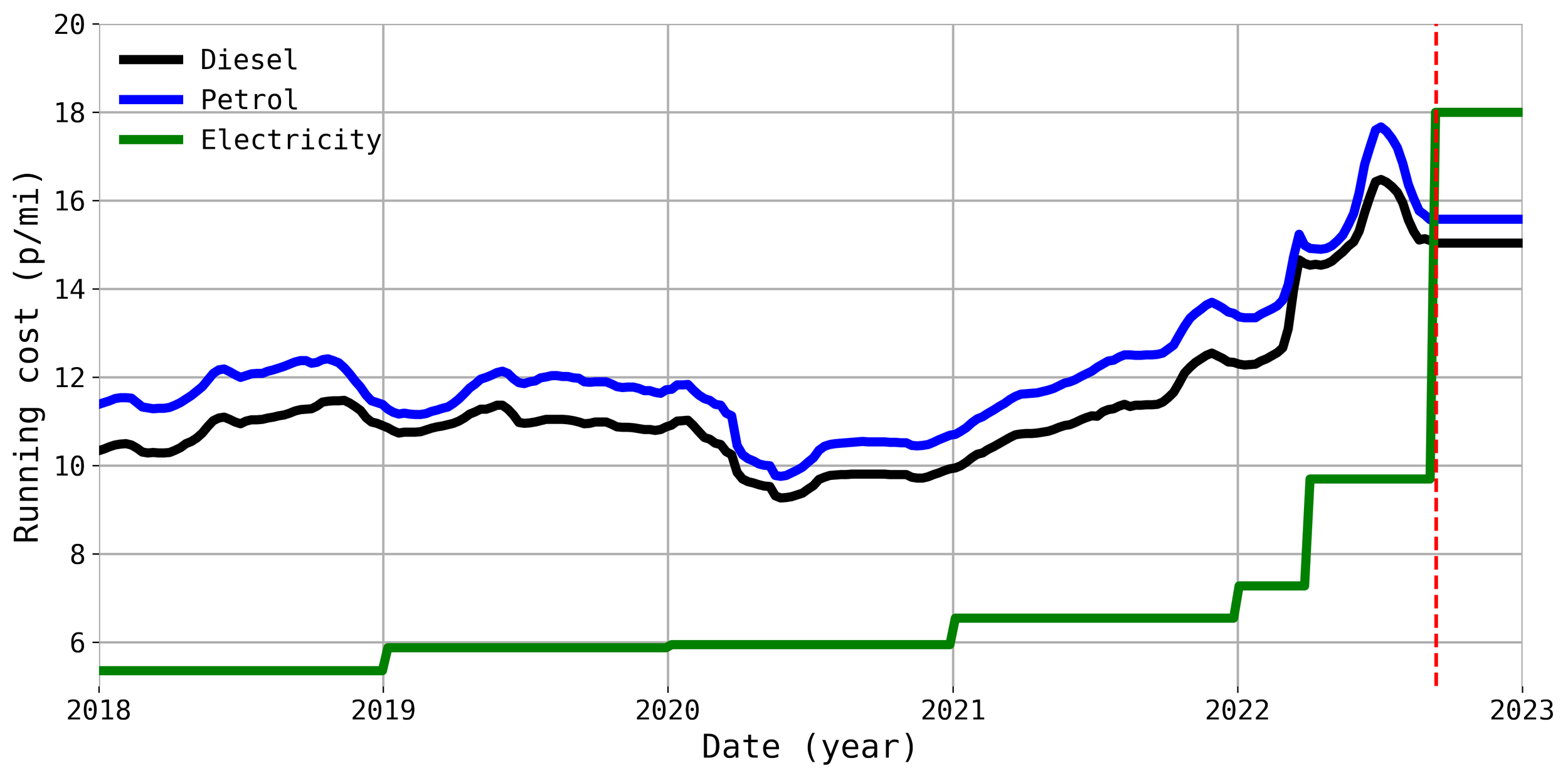

Graph 1: Fuel type running cost per mile comparison, under original price cap announced by Ofgem in late August.

In the last few months, petrol and diesel prices have fallen. At the time of writing, they sat at around £1.67 and £1.83 for a litre of petrol and diesel respectively. At the same time as fuel was becoming cheaper, Ofgem announced that the electricity price cap would rise to an eye watering £3,549/year for a typical household. This would have represented a cost per unit of electricity of 52p/kWh, up from 28p/kWh now and much higher than the 14-18p/kWh range that households have paid for most of the last 5 years. The combination of falling fuel prices and rising electricity prices presents a problem for the economics of switching to an EV.

Support for households

One of Liz Truss’ first acts as Prime Minister was to announce that she would scrap the Ofgem cap and replace it with a new cap, at an amount representing around 34p/kWh for households. This cap is to stay in place for two years. Her package of measures around energy costs mean electric cars still offer households significant savings on running costs if they charge their EV at home and are on a standard variable tariff. [1]

Graph 2: Fuel type running cost per mile comparison, under new energy price cap recently announced by Prime Minister Elizabeth Truss

For drivers who can’t charge at home, the picture may not be so rosy. It seems unlikely that the government’s price cap will cover public EV charging. The price of electricity at public charge points is typically higher than for domestic charging, though some are still free to use. Whilst it must always be noted that the vast majority of motorists are able to charge at home, those that cannot must not be left at the mercy of a wild west style electricity market. It may be that a cap on public EV electricity prices is necessary. A good first step would be to introduce promised regulations that improve transparency around pricing at public charge points, so that motorists are empowered to find cheaper places to recharge. This is an issue that will only grow in importance to consumers, and the new Transport Secretary and Chancellor should be watching closely.

Support for businesses

While the government’s energy bills package keeps EVs competitive on a per-mile basis for most households, there is a different picture for businesses who are starting to invest in electric vans. Our monthly Electric Van Count bulletin showed that in August, 1,000 electric vans were registered in the UK, representing 7% of the market. Behind this figure are businesses who are trying to do the right thing for the UK’s net zero target, but who are already paying 20% VAT on their electricity. The government has promised a 6-month scheme to help with electricity costs, but that is no basis on which to invest in a new electric van. When the government finalises their plans to help businesses with electricity bills, Ministers should consider offering extra support for those who run electric vans or who are considering purchasing an electric van.

Going forward, big questions remain, particularly around the price of oil. At $90 - $100USD per barrel, it is unlikely that the cost of fuel will fall any time soon. However, if the price does fall, it could begin to undermine the UK’s transition. In a sense, it is the risk that this could happen that is most damaging. Every time a consumer chooses to buy a new petrol or diesel vehicle instead of an EV, they lock in years of more pollution. That individual consumer decision is so consequential, whilst also being vulnerable to doubt and uncertainty. If consumers worry that EVs are not a good financial bet, they will simply stop buying them. As well as deliver on policy, Ministers must clearly signal to consumers that EVs will remain cheaper per mile.

There is no reason that the vicissitudes of fossil fuel markets should undermine clean technologies like electric vehicles; the UK has abundant cheap renewable electricity ready to go in batteries of vehicles up and down the country. With the right leadership from the government, the risks of this winter need not imperil the UK’s transition to clean transport. The government’s energy bills package is a good first step, but there is more still to be done.

[1] Most EVs have typically accessed special ‘EV’ tariffs, that give them cheaper overnight rates. These tariffs are harder to get at present. They can offer extremely cheap rates of around 7.5p/kWh which can dramatically reduce the cost of motoring for EV owners even further, though often they come with higher standing charges and daily unit rates are not subject to any price cap, meaning that they typically benefit motorists who do a lot of mileage.