Hyperbolastic or Logistic - Are Fossil Fuels A Virus? Tracing the S curve for UK adoption of electric vehicles

The previous blog showed how well EV take up was following an S-curve (mathematically, a logistic function), in developed markets with stable and unstable policy environments, and in emerging markets. This blog turns to the UK’s experience.

You can reproduce these S-curves, and those for other countries using the dashboard made available with our Global EV Tracker, which is updated as soon as new data is available (usually one month in arrears).

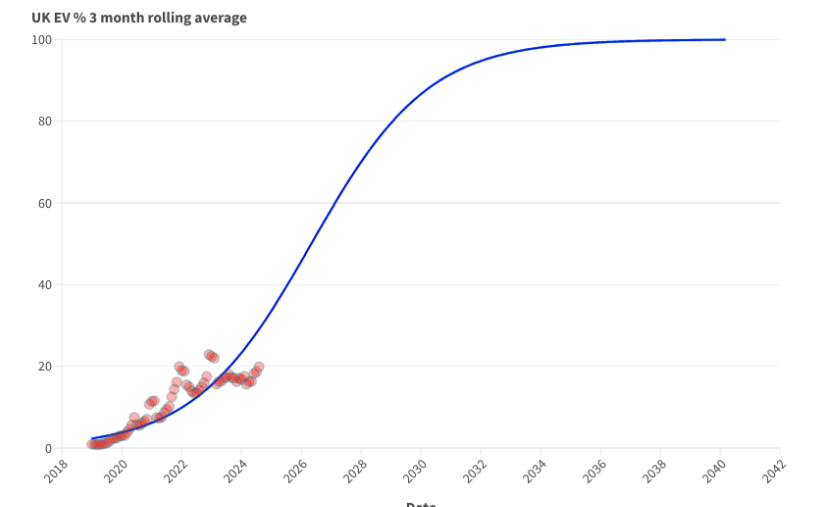

The good news is that a fitted S-curve onto the UK’s trajectory suggests it is still on track to reach 80% market share of battery electric cars by 2030, in line with the Zero Emissions Vehicle mandate.

However the S-curve is not an especially good fit. UK battery electric market share appeared to pick up pace in the second half of 2021 before appearing to slow down in the first half of 2023 and then move backwards from September 2023. Since then - whilst absolute sales were increasing - market share moved sideways faster than it rose until April 2024 when, at least on a 3 month rolling average, it has begun to pick up pace.

EV market share in UK (3 month rolling average) and fitted S-curve to 2040

Whereas in August 2022 the UK might have been expected to hit 80% market share by late 2026, and by this year the expected 80% threshold-crossing had been pushed back to early 2029, although the rate of growth has since stabilised, and the UK remains on course with the ZEV mandate.

This phenomenon is not limited to the UK. Many other countries, including France and China, saw some slowing in the first half of 2023 - although a few, such as Denmark, see none at all.

EV market share in France and China (3 month rolling average) and fitted S curve to 2040

What is causing the phenomenon? We can’t say with certainty, but here are some possibilities.

It could be (at least partly) a result of UK policies

Some public interventions do appear to coincide with a slowdown in the increase of battery electric market share.

Whilst the gradual phase out of the plug-in car grant and the EV home charging scheme, and the announced Vehicle Excise Duty increase seem to have had little if any effect, market share growth went into reverse after the former PM’s announced delay to the phase out of internal combustion engine vehicles. This announcement in reality only allowed a small proportion of internal combustion engine vehicles to be sold between 2030 and 2034. But it was presented as a much bigger shift - and rolling average market share which had been increasing since March 2023, promptly flattened before going into reverse in November 2023. and 12 month smoothed market share has still not returned to the September 2023 level.

This UK-specific “policy messaging” - rather than a policy shift - therefore looks very likely to have had an impact. Other major economies did not see this outright reversal. If we draw a trend line from August 2023, we might be at between 20% and 21% on a 12 month rolling average, rather than between 17% and 18%.

However this growth is not lost forever, and the UK appears to already be making up ground. On the faster responding 3-monthly average, market share is now at 19.9%, its highest level since February 2023.

However other countries have seen a slowing of adoption without the flip-flopping seen in the UK, so this is unlikely to be the whole story.

It could be Covid

Another explanation may be offered by the slump in car sales during the pandemic. With more EVs being bought online than through in-person arrangements at dealerships the relative popularity of battery electric cars soared, but sales of petrol, diesel and hybrid cars cratered, falling 34% in 2020 and only bottoming out in 2022 with sales at 51% of 2019 levels. This could have skewed the S-curve - and from 2022 we’ve been looking at the emergence of suppressed demand and a more realistic adoption curve.

As explained in the previous blog, the S-curve is an adoption curve in a stable system which is free of disruption or disturbance from external conditions. But Covid was one pretty big disruption. And because it restricted car sales in all countries to some extent, it would help to explain why the pattern is seen in most other markets, albeit to a lesser extent.

Incidentally Sweden, the poster-child for lighter touch lockdowns, saw the pace of EV adoption hold up well throughout 2023, whilst other countries saw an emerging slowdown (They have seen declines in 2024, but these are closely linked to the overhasty withdrawal of incentives).

This fits with a theory that ICE vehicle sales may have been less suppressed in countries with lighter lockdowns, giving a “truer” S-curve.

EV market share in Sweden (3 month rolling average) and fitted S-curve to 2040

It could be macroeconomics

Whilst we’re on the subject of external disruptions and disturbances, we’ve had one or two others - inflation, high interest rates and huge hikes in the price of electricity and oil.

The peak periods of galloping inflation, and energy inflation specifically, take place through most of 2022, a period in which EV sales growth remained pretty robust - although the incremental effect on consumer confidence could certainly have impaired the appetite to take on major purchases or the willingness to make a judgement call over switching to an EV (In a market where some electricity generation costs are unhooked from the costs of oil and gas, the cost of charging should rise less steeply than the cost at the pump, making switching to EVs more attractive. However our decisions are never wholly rational, and the impact of EVs on electricity bills is cited by some consumers as a barrier to switching.)

However interest rate changes might better explain the flattening of the S-curve, and why the UK was hit particularly hard.

The UK saw interest rates begin rising from December 2021, though the whole of 2022 and most of 2023 to reach 5.25% in September. In contrast, European Central Bank interest rates did not rise until August 2022 and only reached 4.5% in September 2023, a threshold which the UK had blasted through 4 months earlier.

UK vs Euro area interest rates, last 5 years

In a market which relies on upfront outlay in return for lower costs down the line, it’s unsurprising that this would suppress demand, although it is noteworthy that China, which also saw a slowing in growth, has had pretty constant interest rates.

It could be incumbent resistance

One final possibility is that we are not precisely on an S-curve at all. “Diffusion theory” has been criticised for being based on a one-way information flow. The message sender (the converted EV buyer) persuades the receiver (the ICE vehicle buyer), and there is little to no reverse flow.

We know that receivers are drawing information from many sources, including those hostile to EVs, from sectors of the economy which depend on continued car use (78% of UK oil use is in transport, and 75% of that by road) and a few participants in the car manufacturing industry itself (hi there, Akio Toyoda).

Spreading doubt is the only real go-to for any incumbent faced by a competing product which is not only more effective but also cheaper and healthier. And, given that we’re nearing the end of a massive election year, there's never been a better time to sow fear and doubt.

There’s still time to change the curve we’re on

This can be reflected in the underlying maths, as the logistic function (the pure S-curve) is actually a special case of a “hyperbolastic function”, which can model adoption curves that speed up, plateau and start again.

Whilst the lime green line below shows the pure S-curve, the orange and blue lines show different hyperbolastic trends.

Hyperbolastic vs logistic functions

One use of the hyperbolastic function is in medical statistics, where it can accommodate situations where medical interventions reverse diseases, but without continued treatment, the disease begins to progress again.

So perhaps EVs are the antibodies to the virus of fossil fuel dependence. And running with the metaphor, perhaps the outcome of this fossil fuel addiction is unknown?

Maybe we should reject the phoney predestination of adoption curves altogether and recognise that nothing about the transition is automatic or pre-ordained.

Which means policymakers, civil society, manufacturers (no exceptions, Akio), policy makers, and thinktanks like New AutoMotive all need to redouble their efforts against the there’ll-be-a-better-technology-along-in-a-minute delaying tactics from the virus spreaders.

Electrification is the best technology we have and - from an efficiency perspective - about the best we can have. We need to crush the saboteurs - I mean beat the virus - and deploy the policies and the communications to speed up the switch now.