The mysterious rise in re-used reg numbers

How much do people care about their car’s number plate? Is one generation of people more likely than others to see their registration number as a fashion accessory?

This is the story of a mystery that emerged during analysis of big data about UK vehicles. At New AutoMotive we’re using data about every private registered vehicle to track the UK’s progress switching to electric vehicles and zero emissions road transport. (You can find out more about that here.)

We’re using the MOT database - a database containing details of every annual roadworthiness test carried out in the UK - to track the miles driven by every private vehicle in the UK. (Have a look at the data for yourself here.)

We thought we’d have a look to see whether we could see a change to drivers’ mileage during the coronavirus pandemic. We know that during successive lockdowns, traffic fell to historic lows in the UK. We wanted to see the extent to which this is reflected in the odometer readings taken at annual MOT tests.

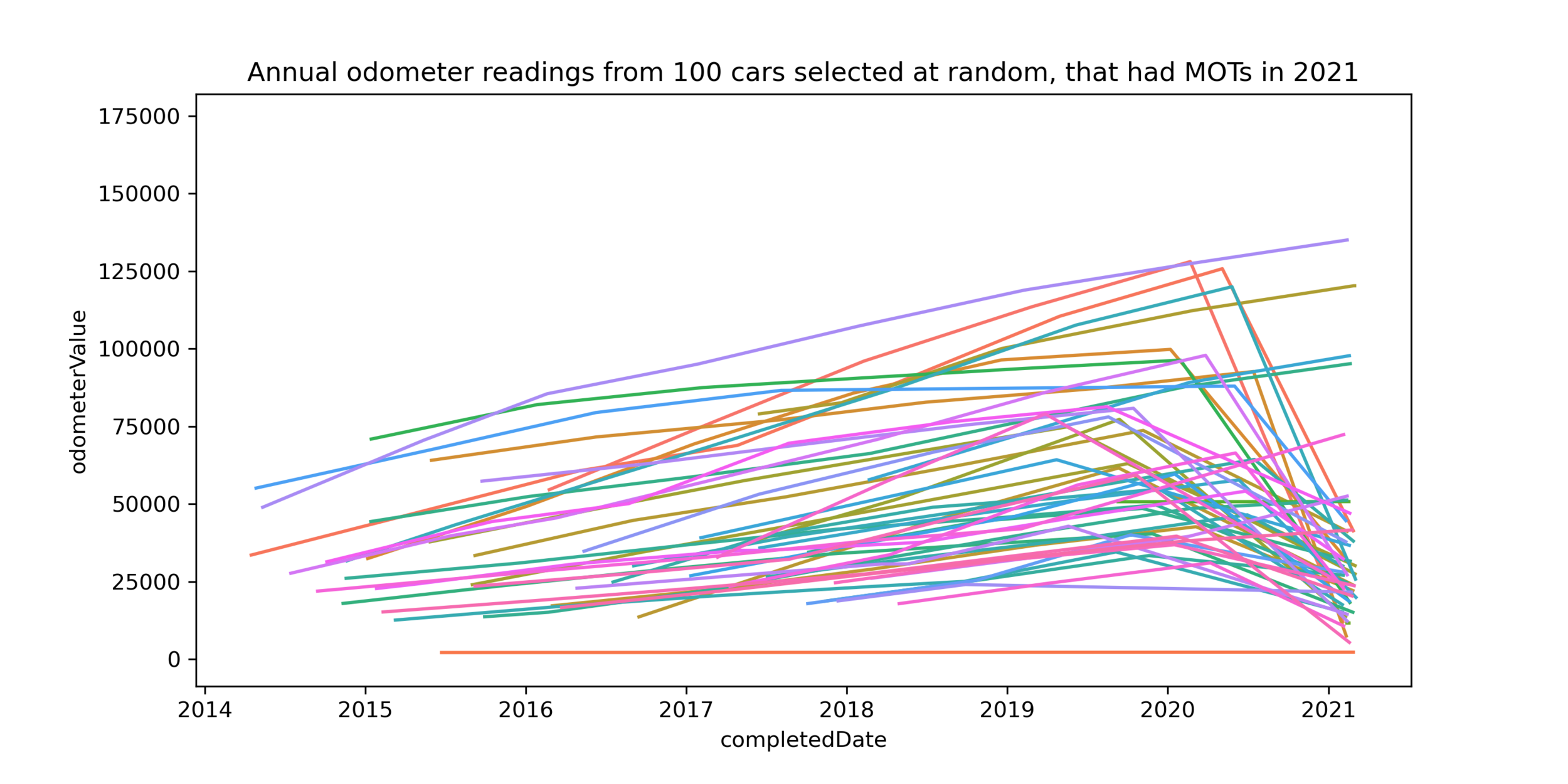

We took a sample of 100 vehicles that had an MOT in the first few months of 2021, and plotted their odometer readings.

Each line on that chart represents a vehicle. At first glance it looks like there’s a significant lockdown effect. But that’s not right. Odometer readings are cumulative, that is: they should either go up, or plateau. Unless a vehicle has been clocked, its mileage should never go down.

Something seemed to have gone very wrong. Those lines should never go down.

After checking our database, and performing some manual inspections, we discovered that the problem was number plate recycling.

Around 230,000 number plates that are (or have ever been) in circulation on MOT-able vehicles (cars that are more than 3 years old) have been used more than once.

In our database, these show up as cars that gradually clock up more and more mileage before dropping down to first-MOT-test levels.

Something still seemed wrong. There are around 64 million vehicles in the MOT database (including many which are no longer on the road). If 560,000 have a number plate that is used on another vehicle, that suggests only 0.8% of vehicles, and 1 car in our sample, should have this problem. But as you can see from the graph above, there are a lot of cars with odometer readings that appear to drop very low in 2021.

That invites the question: why are so many cars with recycled number plates being MOT’ed in the first few months of 2021?

One explanation might be that there was a glut of cars registered in early 2018 that had recycled number plates, which are all coming due for their first MOT.

We can plot the number of cars registered in each quarter with a number plate that has been used twice. Yellow bars represent the first date of registration that is associated with each VRN, and blue bars represent the second, later, date of registration.

The graph is complex, and we should be cautious when we interpret it. It looks like we see a wave of popularity for reusing registrations around the early 2000s. That might be the case, but there are a couple of notes of caution:

The plot misses any vehicles with number plates that the owner is intending to reuse, but hasn’t yet done so.

The plot only has vehicles registered pre March 2018, since newer vehicles do not require an MOT and are not in the database.

One thing we know for sure is that in the early 2000s, lots of people bought cars and have since gone on to keep their number plates. That was the first wave in a pandemic of registration retention.

But the spike at the far right of the graph is curious. If we take registration numbers that were reused after 1st January 2018, which captures that blue spike, we can find the date of registration of the original vehicles:

The mystery deepens. Registration numbers reused in 2018 come mostly from young predecessor vehicles, which were registered around 2012-2018. The typical car stays on the road for over a decade - yet these registrations are all coming from young vehicles. Were they written off? Was this the growth in a new market for old number plates?

If you have a theory you’d like to share with us, or if you’d like to find out more about our work investigating car use and climate change, we’d love to hear from you on: data@newautomotive.org.