The future of the ICE Car Manufacturer - Valley of Death or Market Domination?

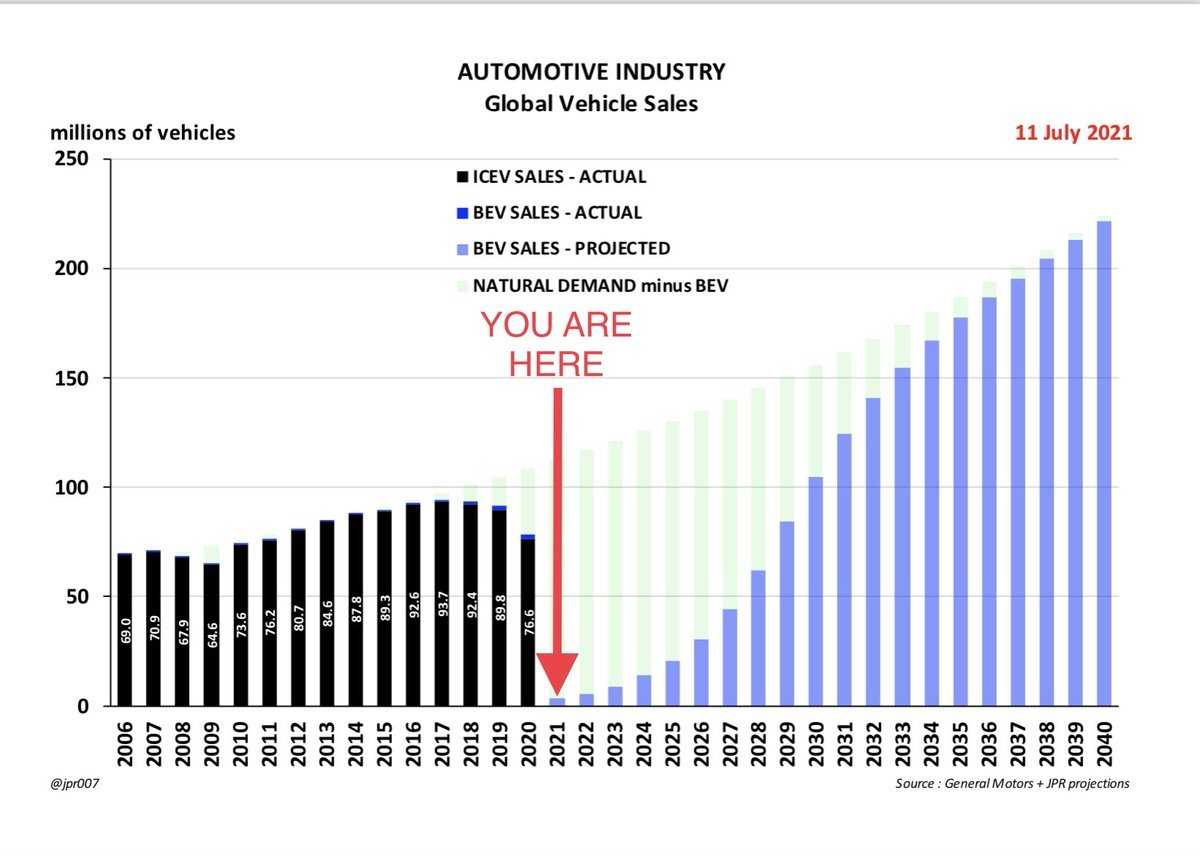

A chart on twitter has divided opinion on how the EV adoption will occur and what it will mean for incumbent manufacturers and new entrants into the automotive market. It is provocatively labelled the ‘Valley of Death’ for traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) manufacturers who cling too long to their preferred technology, even as EVs start to dominate new sales in key markets such as China, Europe – and now the US.

The chart combines three key ideas that provoke controversy:

First, that EVs are now past a tipping point (typically 5% of sales) and so will grow exponentially quickly.

Second, the Osbourne effect is kicking in – people are delaying buying a new car until EVs start to become more mainstream, cheaper and better which only seems to be a couple of years away: as cars typically last 12-15 years, a year or two delay is no big deal when the option of a far better technology is just around the corner.

Third, disagreement on whether EVs are a disruptive technology, or a mere improvement upon the incumbent ICE automobile, remains to be seen. In ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’, Clayton Christensen outlined reasons why incumbent companies are often blind-sided by new technological competitors - with EVs falling into a grey area within the model.

Death Valley or Domination?

What will be the eventual outcome for the incumbent ICE-dominant OEMs (original engine manufacturers) – the likes of VW, BMW, Toyota, Ford, and so on?

If the Valley of Death is as shown in the chart below, then those holding on to ICE sales for future business may face competition not just from EVs built by others, but also from EVs they build themselves. Another compounding factor is the decrease in ‘natural demand’ for personal vehicles, as urban areas increasingly move away from car dependant infrastructure.

Let’s review the first two chart elements (tipping points / Osbourne effect):

It is clear in many key markets (EU, China) that EV sales are well above the critical 5% level with predictions for fast growth in the coming years. In the UK for example latest figures are for EV sales to be 20% of the total, with predictions of 25% or higher for end of 2023 – one in four new sales being an EV.

The problem for incumbent manufacturers is that although there will still be lots of BMW, VW and Toyota cars on the road next year, and the year after – most of these will not be new sales, just five-year old cars being driven around. As car companies chase new growth to create new revenue, that is now increasingly from EVs, not ICE cars.

Many buyers can afford to wait another year or two until they can convince themselves to plunge into EVs. For those with private driveways the option is quite easy – cheaper and more convenient “fuelling” of their cars. This pushes low sales growth of new ICE cars even further downward.

One other point to note is that the “natural demand” of car demand growing by a few per cent per year may also be overblown – the Valley of Death may be even more profound with the upslope lower than shown here.

The Innovator’s Dilemma will determine Winners and Losers

Christensen’s idea noted above is great but missed an important element - hence his back and forth on EVs – he assumed disruption came from beneath, a cheaper, lower-quality (but good-enough) product eventually displacing more expensive, incumbent better ones. To the contrary of his assumption, the car market has been disrupted from above: a high-cost niche technology, a sportscar EV from Tesla, becoming mainstream because of learning curves and better performance – and think not just Tesla S to Tesla 3, but solar panels for satellites eventually becoming available for home rooftops 20 years later.

This has big implications, as the largest car company is the world – by a mile – is Tesla. It’s market capitalisation is bigger than the other nine largest combined.

In addition – of the top ten largest automotive companies three are now Chinese versus none a decade ago, and all are focussed on EV manufacturing. That leaves Toyota, VW, Daimler, GM, BMW and Ford – the previous titans, now scrambling for market share of new EV growth.

We can also assume these erstwhile titans are now trying to aim for leadership in a down market - for ICE cars – that is now suddenly shrinking fast and at best 20% less in size than it was 5 years ago, and with far more competitors – who only worry about EV sales, not the legacy effort and cost of ICE manufacturing.

Had the incumbent car industry embraced EVs and shed their ICE legacy - it is likely that their brand, expertise and supply chains of component parts and dealerships would have reigned supreme in the new world of electric vehicles.

In contrast, they have done little of the above.

They have resisted the new technology of battery and metal supply chains, and clung to business-as-usual modes of selling cars via dealers and forecourts and focussing on new ICE (or clunky hybrid) models.

In the short-run this can look successful as EV sales still are a minority, and the on-the-road models still look very ICE-like.

But recall – all those cars on the road today have been already bought, and no longer provide growth, and all the new technology from Tesla and the Chinese entrepreneurs along with their manufacturing horsepower are the current future momentum of transport.

Our bet is that the Valley of Death is more likely, and that EVs have turned out to be a disruptive technology to the car manufacturer incumbents – not a sustaining one.

And that is because in the wider transition of energy from extraction (fossil fuels) to manufacturing (wind, solar, batteries), those who really embrace it win, and those who part or superficially embrace it, lose.